|

TOMPION no.145.

A true Dutch striking English clock.

By:

Melgert Spaander.

Table of contents:

Description.

Dutch

striking.

Striking

parts.

Strike

No Strike.

Reconstruction

of the pull repeat.

Bolt & Shutter

maintaining power.

Case.

Observations.

Postscript.

Acknowledgments.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

At the

Drents

Museum

in Assen (The Netherlands) one can find a modest but distinguished longcase clock among many fine examples of Dutch furniture. After

closer observation the dial of this clock appears to bear not a Dutch

name but the signature: Tho=Tompion Londini Fecit.

Immediately the question arises as to how this work of art, made by

this London clockmaker of repute, came to be in the eastern province

of Drenthe? Peter Schoonewille, the Drents Museum’s curator, has

explained that many years ago this clock was bequeathed to the museum

by the old aristocratic family de Vos van Steenwijk, together with its

family archive. It was said that the clock had been in the family

estate for many years. The importance of the clock among the Museum’s

collections was made clearer following a visit by J.H. Leopold of the

British Museum who was able to examine it and underline its special

qualities.

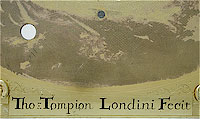

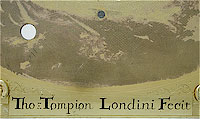

Fig. 1a (click to enlarge)

The dial signature on Tompion's No 145.

The decision was taken to restore the case and following this attention

was paid to the movement in order that it could run safely. The

movement appears to be of a month’s duration and has a complicated

striking mechanism, which is fully recognizable as a Thomas Tompion

design. Although the clock was functional, the many empty holes in the plates suggested that several parts were missing. A detailed

examination to determine its original construction was carried out and

documented. Finally, with the help of Jeremy Evans at the British

Museum we had the opportunity to compare this clock in detail with all

the Tompion clocks he has documented extensively throughout the years.

As a result of this work the clock has given away many of its secrets

and made it possible for the striking mechanism, the complicated

pull-repeat and the bolt & shutter maintaining power to be

reconstructed at some future date. In the mean time, the restored clock

can be admired at the Drents Museum in Assen in expectation of its

possible reconstruction. The clock has also been on display in the

recent Huygens Legacy Exhibition at Palace 'Het Loo', exhibit No.76.

) )

DESCRIPTION

DESCRIPTION

The signature on the

clock ‘Tho=Tompion Londini Fecit’ is engraved on the base of the dial (Fig. 1a)

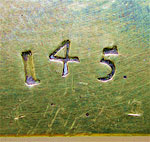

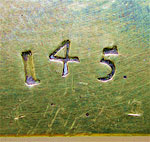

and the number 145 is stamped on the left side of the trunk door (Fig.

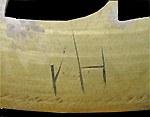

1b) and also on the base of the back plate (Fig. 1c). There are also

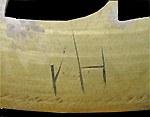

the initials VH scratched on the back of the dial components in

several places (Figs 1d&e).

Fig. 1d & 1e. (click to enlarge)

The

initials VH engraved on the back of the

date ring (top) and the seconds chapter ring.

The clock appears to have been made within

the period 1685-1690. The fire-gilt 11 in. square dial (Fig. 1f ) has

four fire-gilt cherub spandrels and features both wheatear banding

along the borders and engraving between the spandrels. There is a

seconds ring and date aperture and the chapter ring has markers for

half-quarters, quarters, half-hours (Tompion’s favored cross style)

and minutes (numbered every five). The strike/no strike lever is

situated at IX. The blued steel hands are of a design commonly used by

Tompion.

Fig. 1b & 1c (click to enlarge)

The number stamped on the door edge and the lower edge of the back plate.

The case of the clock is of oak, veneered in walnut, with wheatear

banding on all sides and inlaid on the front with colored full floral

marquetry. The originally rising hood, has been altered to a sliding

hood with front door. The hood columns are missing. There are frets in the side windows and a frieze runs around three sides below the top

moldings. Fixing marks on the top of the hood could have been for a

dome or cresting. The plinth has been altered and runs over the

marquetry of the base (Fig. 1g).

Fig. 1g (click to enlarge)

Marquetry case of

Tompion’s No.145.

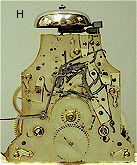

The month-going movement (Figs

1h,i,j&k) has specially tapered plates, separated by six knobbed

pillars. Holes in the pillars slide over pins in the seat board, the

whole being secured by an adjustable hook on the case back board. The

bolt & shutter maintaining power, activated by a cord inside the trunk,

is all missing. The escapement is recoil anchor and the seconds-beating

pendulum is adjusted by a round nut with Arabic numbers. The movement

has an inside rack for Dutch striking: the hour on a large bell, and

at the half, the coming hour on a small one. Locking is done on the

rack and the snail is on the hour wheel. The striking train is on the

left whilst the hammers are on the right. There is also a passing-strike

mechanism, the first quarter on the large bell and the third quarter

on the small one. Repeating work by pulling a cord on either side of

the trunk, accurate to half an hour, is all missing.

Fig. 1f (click to enlarge)

The dial of Tompion's No 145 before and after

restoration.

The following repair marks have been found

on the movement:

g de groen 17 October 1896

J vd Kolk 14 sept 1900

J Daverschot J Post 16.9.28

P Kluin 3 nov 1930

Schmole 1941 Groningen

DUTCH STRIKING

DUTCH STRIKING

In the literature

‘Dutch striking’ is mostly defined as striking the hours on a large

bell and at the half-hour on a small bell. Only rarely is it

further

indicated

)

how many blows

are given at a certain half-hour, and that many Dutch clocks give one

blow at the quarters on either the large or the small bell. In Holland

three kind of striking methods are in use, of which the third type has

two variations. )

how many blows

are given at a certain half-hour, and that many Dutch clocks give one

blow at the quarters on either the large or the small bell. In Holland

three kind of striking methods are in use, of which the third type has

two variations.

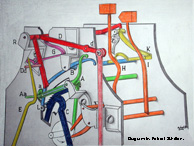

Fig. 1h, 1i, 1j & 1k.(click to enlarge)

Four views of the movement The number of the clock can be seen clearly

at the bottom of the back plate

(Fig. 1k).

If literally translated into English, these

Dutch terms would be:

1. ‘Single strike’

|

At the hour the right number of blows on

a bell. |

|

At the half-hour 1 blow on the same bell. |

2. ‘Double strike’

|

At the hour the right number of blows on

a large bell. |

|

At the half-hour the number of blows of

the coming hour on a small bell. |

3A. ‘Quarter strike’

|

At the hour the right number of blows on

a large bell. |

|

At the first quarter 1 blow on the same large

bell. |

|

At the half-hour the number of blows of

the coming hour on a small bell. |

|

At the third quarter 1 blow on the same

small bell. |

3B. ‘Quarter strike’

|

At the hour the right number of blows on

a large bell. |

|

At the first quarter 1 blow on a small bell. |

|

At the half-hour the number of blows of

the coming hour on the same small bell. |

|

At the third quarter 1 blow on the same

large bell. |

In Holland the

clock strikes the coming hour at the half-hour. This reflects the way

that the time is told in the Dutch language. In Holland, at the

half-hour one counts towards the coming hour: ‘half three’ means 14:30.

In England at the half-hour one starts from the passed hour: ‘half

past two’ means 14:30. All together it makes a difference of an hour.

The English version of 3A (not found in Holland) strikes as follows:

3A. ‘Quarter strike’

(English version)

Clock No.145

strikes according Dutch version 3A, so at the half-hour the number of

blows of the coming hour are struck. In a rack-striking clock, the

orientation of the hole in the hour hand boss is essential in this

matter

Fig. 2a, 2b & 2c.(click to enlarge)

The snail, the snail disassembled and the hour hand fitting on the hour

pipe

(see following).

STRIKING PARTS STRIKING PARTS

If, as is the case in

No.145, the pipe of the hour wheel (with its square shoulder for fixing the hour hand) is made in one piece together with the snail, the

number of blows is fixed to the time the hand is showing

(Figs 2a,b&c). Normally the square fixing hole is aligned along the axis of the hand.

With such a ‘normal’ hand, No.145 would have struck the number of blows of the passed hour, at the half-hour, so following the English method

3A.

However, the position of the fixing hole in the hour hand of No.145 is

turned 15º (½ hour anti-clockwise) (Fig. 2d) and because of this the

clock strikes the coming hour at the half-hour in the Dutch way. Its

design does not differ from other hands leaving the workshop of Tompion at the time, except in this detail. It would be interesting to

know if this particular hand (Figs 2e&f ) was made in London or later

in a workshop in Holland.

Fig. 2 d (click to enlarge)

Square fixing hole in the hour hand, offset 15° to ensure correct Dutch

striking.

Fig. 2 e (click to enlarge)

Detail of hour hand before repair.

Fig. 2 f (click to enlarge)

Detail of the minute hand.

Of the Tompion clocks we have seen, No.311 at Lyme Park bears the

greatest resemblance to No.145 with its pull repeat and Strike/Silent

on the dial. The hour hand is a ‘normal’ one and indeed it strikes the

English way at the half-hour. The catalogue of clocks at Lyme Park

however indicates that it has Dutch striking. English clocks exported

to the Netherlands up until c.1750, have the hour hand with a round

hole to be fixed on a round shoulder of the hour pipe by a tiny screw

through a little hole in the hand (or steady pin in a small slot). By

making just another little hole (or slot) 1/24 of the circumstance

next to it, the striking system is modified to suit the Dutch market.

Screwing a separate snail on the hour wheel was another way of solving

the problem. With an extra hole in this part, the same adaptation could

also be obtained.

S(TRIKE) N(O STRIKE) S(TRIKE) N(O STRIKE)

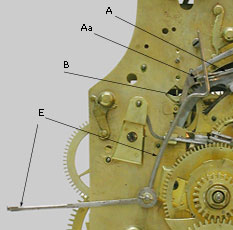

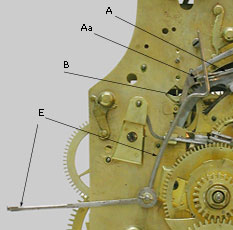

With lever (E) in

position N (Figs 3a,b&c), the clock will be prevented from striking

during normal running. The bent arm of lever (E) turns the horizontal

pivoted pin (Aa) of the lifting piece in such a way, that this pin can

no longer reach the rack hook (B) to release the rack (Figs 3d, e & f ).

Thus the lifting piece (A) rises and drops of every half an hour

without any effect, whilst the striking train is kept available for

repeating.

Figs. 3a & 3b (click to enlarge)

a)

Detail of the Strike/No strike slot in the dial.

b)

The Strike/No strike lever behind the dial.

Fig.

3c (click to enlarge)

Deatail of the Strike/No strike system, showing the lever E, the

pivoted pin Aa, and the rack hook B.

end

Fig.

3f (click to enlarge)

Lifting piece A with pivoting pin.

End

of this section, click

here to continue.

|

Back to previous section.

Back to previous section.

RECONSTRUCTION OF THE PULL

REPEAT

RECONSTRUCTION OF THE PULL

REPEAT

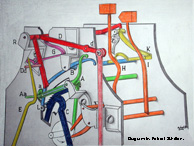

The repeat mechanism is completely missing. By starting with the empty

holes in the plates and studying striking trains of other Tompions,

gradually we were able to reconstruct its unusual operation (Figs

4a,b&c).

If either cord to the left or right side of the case was pulled during

the first half of an hour, the large bell would sound the passed hour

and during the second half the small bell would sound the coming hour.

The multi-function repeat lever (D) was located in the upper left

corner, pivoted in the back plate and a cock (R) screwed on the front

plate. The strong spring (G) screwed on the cock holds this lever in its

upper position. On pulling the cord for repetition, the main arm of

lever (D) comes down to press with pin (d) on the scrolled back end of

the lifting piece (A), resulting in a normal striking procedure as every

half an hour.

However just a few minutes before every half-hour the repeat work is

susceptible to failure as the strike changes over from one bell to the

other or from striking 2 or 3 (for example).

4b

Figs. 4b. (click to enlarge)

Views of the movement showing

the area where the repeat mechanism is missing.

Fig. 4b. (click to enlarge)

Diagrammatic representation of the missing repeat mechanism. Compare with

fig 4a.

If the rack (C) falls on the snail at that very moment, the gathering

pallet could jam on a rack tooth, so blocking the striking train

completely. This problem was effectively solved by Tompion by bringing

lifting piece (A) into use for repetition. A few minutes before the

clock strikes, the lifting piece (A) moves upward, meanwhile blocking

with its hook (Aa) the frontal arm of repeat lever (D). As a consequence

the repeat cord can not be pulled for a short period of minutes. After

the critical transition has passed and lifting piece (A) has dropped

off, the cord is free for repetition again. In addition, by using the

warning, the rack was given enough time to drop properly onto the snail.

4c

Fig. 4c. (click to enlarge)

View of the movement with the front plate removed. Compare with Fig 4b

for the missing repeat work.

So as to enjoy a good night’s rest, the S/N lever (E) not only silenced

the striking train but the passing strike as well. In position N the tip

of lever (E) moved pin (Dd) on the frontal arm of repeat lever (D)

slightly to the left, so that its other arm between the plates was

holding back the quarter hammers (H&I) by means of an intermediate lever

(K) pivoted in the back plate.

However, to achieve a repeat in position N, activating the lifting piece

(A) is not enough; the scrolled back end of rack hook (B) has to be

pressed by pin (d) on the main arm of lever (D) as well. This is

necessary, because in position N, lever (E) has turned away pin (Aa) in

lifting piece (A), taking away its connection towards rack hook (B) to

unlock the rack (C) and release the striking train.

BOLT & SHUTTER MAINTAINING

POWER

BOLT & SHUTTER MAINTAINING

POWER

All the holes for the parts needed still exist. It is possible to

restore the mechanism in Tompion style whilst dealing with the lack of

space on the front plate, as found on other clocks made by him.

CASE

CASE

Fig. 5. (click to enlarge)

The hood showing the marquetry.

Traces remaining in the hood (Figs 5a&b) prove that it was made as a

rising hood with a fixed glazed front panel and columns on the corners.

At an early stage it was converted to a hinged door, locked by a key.

Figs. 5a (click to enlarge)

Traces of the former rising hood and pillars.

Remaining saw marks (Fig. 5c shows one example) and the corresponding

wood veins of separate parts, formerly one piece, are evidence of this

procedure. This whole operation made the sometimes daily operated S/N lever on the dial

accessible without lifting the hood.

Fig. 5b. (click to enlarge)

Internal view of the hood, showing the cutting of the door

Figs. 5c. (click to enlarge)

Detail of the saw marks made when the hood was cut to make a door, and

the corresponding wood veins of separate parts, formerly one piece.

For securing the hood, a pin fixed at the back of the door enters a hole

in the trunk when closing this door which is then locked by a key. This

assembly (Figs 5d&e) has also been found on other Tompion cases.

Fig. 5d & 5e. (click to enlarge)

Location pin in door frame and corresponding hole in the case upstand.

In a later period the hood was modified from rising to sliding and

locked by a turn catch (this can be seen in Fig. 5b). However the

remains of a lock with its spring (Fig. 5f ) are witness to the original

rising hood construction. The columns appear to have been removed only

recently. Traces on the top of the hood (Fig. 5g) suggest the former

presence of a dome or carved cresting on three sides.

Fig. 5f. (click to enlarge)

Marks left on the back board by the removal of the original catch and

spring for the rising hood.

Fig. 5g. (click to enlarge)

Tel-tale marks left on the top of the hood by removal of a cresting

or dome.

Both sides of the trunk have little brass tubes

for guiding the cords via brass pulleys, mounted on the back the right

of the upper molding, towards the repeat mechanism (Figs 5h&i).

Fig. 5h. (click to enlarge)

hole for brass guide tube for repeat cord, in the right hand side

of the case.

The

original feet are missing and recently skirting has been applied which

covers the bottom of the marquetry panel.

Fig. 55. (click to enlarge)

Melgert Spaander, Robert Schilten and curator Peter Schoonewille studying

the case at the Drents Museum.

OBSERVATIONS

OBSERVATIONS

Apparently Tompion’s clocks

No 131, 311 & 387 contain almost identical

constructions of the repeat work designed for No.145. The movement of

No.311 at Lyme Park (Fig. 6a) is also executed with the same specially

shaped plates (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6a. (click to enlarge)

Tompion's no. 311 at Lyme park, National Trust.

Fig. 6b. (click to enlarge)

View of the movement of Tompion's no. 311, with similar shaped plates.

Though Tompion movements may have strong resemblances, they often

diverge in serial number. In Jeremy Evans’ view this indicates that

Tompion used to make several standard movements and dials which he kept

‘on the shelf’ in his workshop ready for finishing when required. The

countless conversions and adaptations we found in No.145, verifiably

made at a very early stage, confirm Jeremy’s ideas in this matter.

When William III

became King of England in 1689, Tompion found him to be a great lover

of technical instruments and he became an important client. The King

ordered the most complicated movements from Tompion in precious

eye-catching cases to embellish his sumptuous palaces. William also gave

away clocks or watches as gifts to many of his international relations

and acquaintances, so objects signed by Tompion appear on the scene

all over the world. Being Stadholder of Holland, William III acted as

a mediator for Tompion and gave him opportunities to increase his

export activities to the Netherlands and other parts of continental

Europe.

On 6th May 1697 Tompion gained a passport for

traveling through the

Netherlands together with a Dr Pragest.

)

His introduction to wealthy Dutch families may well have resulted in a

number of important orders. )

His introduction to wealthy Dutch families may well have resulted in a

number of important orders.

According to its dating of 1685-1690, based on its number and

appearance, No.145 would have been too old to be made specifically for

the visit of 1697. This implies that either Tompion exported this clock

in an earlier period, or that he adapted an older clock especially for

Dutch clientele, to be sold during his voyage.

The noble family de Vos van Steenwijk was the last owner of No.145, but

they may have also been the first. The family archive possibly contains

relevant details regarding this subject. The lay out of the striking

parts shows at least, that No.145 originally was made to be used in

England.

In both Holland and England was a demand for clocks fully striking at the hour,

as well as at the half-hour on different bells. Essentially most English

clocks with so called Dutch striking, have nothing to do with Holland at

all, except the exported ones of course. It may well be that this

striking method formerly had its own name in England, and fell into

disuse together with the device itself. It would be interesting to know

if the expression ‘Dutch striking’ was used in the seventeenth century,

or originated as late as the twentieth century. Generally speaking,

grande sonnerie is not practiced in clocks made in Holland, probably

because this way of striking would only lead to confusion in determining

the time by sound.

This investigation of Tompion’s No.145 throws extra light on the

practices of clockmakers on both sides of the English Channel during the

period when William III was at the same time Stadholder of Holland and

King of England.

POSTSCRIPT

POSTSCRIPT

The reconstruction of the missing mechanism in Tompion’s No.145 has yet

to be carried out. It is important that any future work is reversible, and

the original are not altered.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Robert Schilten, Jaap Boonstra and Michael

Applebee for their much appreciated assistance. Also, I am indebted to

Peter Schoonewille of the

Drents

Museum in Assen, Clair Bissell of Lyme

Park (National Trust), and J.H. Leopold and Jeremy Evans of the British

Museum. It would have been difficult to complete this work without their

help.

Zutphen, The Netherlands, Oct. 2004.

Notes.

1. Hans van

den Ende, Dr Frits van Kersen, Maria F. van Kersen-Halbertsma, Dr John

C. Taylor and Neil R. Taylor, Huygens’ Legacy, catalogue of an

exhibition held at Paleis Het Loo, (Castletown, Isle of Man: Fromanteel

Ltd, 2004), pp.218-219. (back

to text)

2. See, for example, R.W.

Symonds, THOMAS TOMPION his life and work, (B.T.Batsford, 1951), p.115

and Tom

Robinson, The Longcase Clock, (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors Club,

1981), p.132. (back

to text)

3. Symonds, op. cit.,

p.41.

(back

to text)

back to text.

back to text.

|