|

From

CUCKOO CLOCK Table of contents: The Museum of the Dutch Clock in Zaandam is holding a temporary exhibition of clocks from the Black Forest in Southern Germany. The title of the exhibition is “From Cuckoo Clock to Regulator: Clocks from the Black Forest (1740-1900)”.

The visitor is met by a traditional clock-man. The traveling clock merchant was once a familiar figure in the Black Forest. On his back he carried a wooden pannier (so-called “Krätze”) containing his wares. One of the first clock merchants, Joseph Winterhalder, reached Holland in 1720. He founded a company of clock and bird merchants in Gutenbach. A special clock carriers company for trade with Holland was formed in 1760. Trade was also carried out with other foreign countries such as Turkey, Egypt and North America. Painted tin figures dressed in historic costume and with a clock on the front were made up until the end of the 19th century. These clock-men (so-called “Uhrenmänle” or “Uhrenträger” often stood in the clockmaker’s window for recognition purposes and were also known as shop-window figures (so-called “Schaufensterfiguren”). 31 independent clockmakers were active in the Black Forest in 1740. They were originally farmers who produced clocks during the winter months in their homes. The first clocks were made of wood and had a regulating foliot (so-called “Waaguhren”). Foliots had been used in turret-clocks (so-called “Türmeruhren”) since the 14th century. A quarter hand was added to the dial, under the hour hands, around 1700. The clock was encased in a case (so-called “Kastenuhr”) and fitted with a locally produced glass bell. Christian Wehrle, originating from Simonswald, replaced the foliot by a pendulum in 1740. This pendulum was positioned in front of the dial (so-called “Vorderpendel”, “Kuhschwanzpendel” or “Kurzschwanzpendel”). Around 1760 the pendulum was hung between the movement and the wall plate as in a Frisian stool clock. Finally, around 1830, the pendulum was mounted within the movement. Although originally made only from wood (so-called “Holzräderuhr”), escapement wheels were later replaced by brass ones. In the so-called “Holzgespindelte” clocks, all the wheels are made of brass and the arbors of wood. From about 1850, all arbors were made of steel.

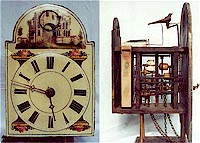

Towards the end of the 18th century, a movement was invented whereby the hour and quarter strikes were produced by one mechanism. In this case the pin wheel was fitted with pins on either side, respectively 12 and 4 pins. The dial mechanism moves a lever which then gives the correct number of strikes. Clocks with this special striking mechanism were called “Surrer” after the snoring sound produced during striking. The most common dial form found in Black Forest clocks between 1780 and 1880 was the arched form. Initially they were painted or pasted over with paper, although during the 19th century the lacquered dial (so-called “Lackschild”) became very popular; these usually depicted floral patterns (so-called “Rosenuhren”) and often had a painted column, on either side of the chapter ring. Some clocks also bore the names of the bride and bridegroom. Clocks, which were decorated with illustrations of fruit (so-called “apple clocks”), were often exported to Holland. Painting the dials was usually the work of women. Gummed pictures depicting landscapes or towns (so-called Abziehbilder”) were also used from 1845 onwards. Besides dials made from wood, metals and glass, porcelain was sometimes used (so-called “Porzellanschild”). From 1856 onwards, small clocks in particular were produced with a porcelain dial having a diameter of 7 to 9 centimeters (so-called “Jockele”). These Jockele clocks were often exported to Holland and England. The biggest supplier of porcelain dials was the brick factory J.F. Lenz in Zell a. Hamersbach. The so-called “Sorguhren” with a diameter of 3 to 4 centimeters, are the smallest clocks produced in the Black Forest. The first ones were made by Franz-Joseph Sorg (1807 – 1872) of Neustadt. The enameling of dials was a technique which originated in Paris and Vienna. End

of this section, click

here to continue.

|

Although expensive and therefore only for the rich, musical clocks became a specialty of the Black Forest.

They were equipped with bells (so-called “Glockenspiel”), organ pipes (so-called “Flötenuhr”) or strings (so-called “Harfenuhr”). Musical clocks with glass bells were first made around 1770 by Peter Wehrle in Simonswald. His son, Christiaan Wehrle, used metal bells and perfected the musical clock. He also made the first organ clock with organ pipes. The Baroque style gilt dials produced by Matthias Faller (1707 – 1791) were especially attractive. A romantic illustration shows a Black Forest music clockmaker’s workplace around 1825. Included in the exhibition is an example of a beautiful “Flötenuhr” containing a wind organ mechanism dating from around 1820 (so-called “Trompeteruhr”. The instrument measures about 60 centimeters and has a music programme of 2 x 8 melodies. The melody index is signed by Antony Düfner.

The earliest cuckoo clock is reputed to have been made around 1730 by Franz Anton Ketterer from the Black Forest. The cuckoo call is reproduced by two organ pipes of different lengths (14 and 17.5 centimeters) and powered by bellows. Later, a mechanism was introduced to move the bird and open the little door on the dial. Early examples of this type date from around 1760.

The characteristic design of the signalman’s house (so-called “Bahnhäusle) was applied to the cuckoo clock around 1850, after a design by Friedrich Eisenlohr (1805-1854) of Karlsruhe. The design is characterized by a gable with saddleback roof and surrounded by fretted or carved woodwork depicting foliage. The weights are usually in the form of fir cones. The “Bahnhäusleruhr” succeeded the “Lackschilduhr”. The exhibition contains a wide selection of examples such as a simple “Lackschilduhr” with a cuckoo in the gable, weather houses and clocks with hunting trophies. A neo-gothic example of a cuckoo clock signifies the quest for German unity. Medieval cathedral architecture was seen as the soul of the Germanic race. The first frame clocks (so-called “Rahmenuhren”) were made around 1750 and had illustrations behind glass (so-called “Hinterglasmalerei”). Clocks with paintings in oils on zinc were being made in 1830 and became very popular around 1880. Frame clocks made with pressed brass, stained and sometimes chromium-plated, became popular around 1840. Architectural cases with porcelain columns on either side of the enamel dial (so-called “Biedermeieruhren”) were produced from 1860 onwards for city dwellers. Painted clocks depicting people or animals whereby the eyes were moved backwards and forwards by a mechanism connected to the pendulum (so-called “Augenwender”) were also popular. The exhibition also contains two examples of portraits of women in oriental costume; these were intended for foreign markets. Clocks (so-called “Figurenuhren”) with figures powered by a mechanism were specially made for rich citizens. These were originally modeled on church clocks such as the one in Neurenberg. One of the oldest figure clocks shows a capuchin monk ringing the bells (so-called “Kapuziner”). Many other moving figures were also popular; some examples are the bell hammerer (so-called “Glockenslägeruhr”), the trumpeter (so-called “Trompeteruhr”), the watchman, the butcher (complete with cattle for the slaughterhouse), the executioner who beheads a delinquent (so-called “Enthauptungsuhr”), the Turk complete with turban, moving eyes and chin, the dumpling-eater (so-called “Knödelfresser”) and the fighting goat bucks. Friedrich Dilger and Michael Dorer were two of the most famous early producers of figure clocks. The executioner figure clock was made after 1800 and the “Knödelfresser” from 1880 onwards. Factory produced wall clocks based on the Viennese regulator were being made around 1860 and became a big international success. The Dutch were unable to compete with the production of these cheap “horse clocks” with their metal 8-days mechanism. The pendulum was contained within the longer case and visible through a glass window. The clocks were powered by a spring and often equipped with a gong striking mechanism. Especially popular, was the 40cm long miniature regulator made by Michael Bob in Triberg. The Black Forest also produced numerous turret-clock factories; many of these turret-clocks were destined for Holland. The exhibition recently being held at the Museum of the Dutch Clock consists of at least forty clocks from private collections, supplemented by clocks on loan from the National Museum from Musical Clock to Street Organ in Utrecht, the Dutch Gold, Silver and Clock Museum in Schoonhoven and the Deutsches Uhrenmuseum in Furtwangen. The aim of the exhibition is to illustrate the technical evolution as well as the diversity in type and form.

Museum of the Dutch Clock

|